Inside the exhibition

Inside the red mirror

This is a virtual space where you can imagine your own view of Mars: god, symbol and planet in its different metamorphoses. You may have visited the exhibition or simply clicked on to this page skipping between links and other everyday internet browsings. It depends on how much time you want to spend, how much concentration is required and how curious you are.

We’ve devised a few prompts to help you immerse yourself in the fascinating experience Mars can inspire as a mirror of our home: planet Earth. A mirror of our past, but also of a dizzying present and future. You already know climate change is our sword of Damocles. There isn’t much time left to reverse the situation. The desert is advancing in the cradle of a humanity that is rediscovering the extraordinary connection between all living creatures, in the midst of a pandemic, with a wounded planet mired in the Sixth Extinction. Yet we can still think up new Utopias, stories inspired by emotion and wonder. After all, nobody knows which of the possible futures will eventually prevail.

A text by Juan Insua, curator of the exhibition.

The voice of the meteorite

I am a rare stone. Call me KSAR Ghilane 002 or whatever name your imagination conjures up. I come from Mars. I have travelled through space for thousands of years until I reached my unexpected destination in the desert you call the Sahara. I was discovered as a result of the insatiable curiosity for exploring that is inherent to your species. Now you can see one of my fragments. I come from the deepest strata on the Red Planet. I have a story to tell you. Because I am also a meteor, like the storms, typhoons and hurricanes you can’t control.

Meteorite KG 002 Discovered in 2010 in the Sahara Desert, near Ksar Ghilane, Tunisia, by José Vicente Casado and David Allepuz; and identified by Jordi Llorca, professor of Chemical Engineering at UPC. José Vicente Casado Martínez collection.

Meteorite KG 002 Discovered in 2010 in the Sahara Desert, near Ksar Ghilane, Tunisia, by José Vicente Casado and David Allepuz; and identified by Jordi Llorca, professor of Chemical Engineering at UPC. José Vicente Casado Martínez collection.

A day on Mars

Martian weather. Marta Llinàs (Estudi Canó) / Pixelon - Sergi Mussull, 2021.

Alien maps

Just imagine how much work is involved in mapping a planet more than 200 million kilometres away when the distance is shorter during periods of opposition. Centuries of observation have resulted in a map that has undergone many changes since the end of the 19th century when Giovanni Schiaparelli drew a dense network of linear structures he called canali. This led to their mistranslation into English as canals, suggesting they were artificial in origin, rather than channels, which would be more appropriate as it refers to a natural structure. This is one of the most widespread misunderstandings in the history of astronomy: Mars would be inhabited by an ancient canal-building civilisation in its death throes. This is what the American astronomer, Percival Lowell, believed and he spent much of his life trying to prove this theory. The development of telescopes and probes sent to Mars proved Lowell wrong, but the Martian canals, or channels, have provided a rich source of inspiration for science-fiction stories. However, Lowell showed great foresight when he compared the deserts on Mars to the gradual desertification of planet Earth. The geological history of Mars is also the result of profound climate change.

The music of the red mirror

The ancients believed that the planets played mysterious music from outer space. The harmony of the celestial spheres that can be picked up by the most finely tuned ears. We may never hear this subtle melody, but we do have different sources available to help us imagine what the music of the Red Planet may sound like. The predictable path is to turn to Gustav Holst, the songs of David Bowie and Nick Cave, or to listen closely to the sounds of the Martian wind captured by NASA. Instead we decided that Mars. The red mirror, needed its own soundtrack. The creation of atmospheres that will give us a greater insight into each section of the exhibition. This is an excerpt from the soundscapes created by Nico Roig. A choir of distant voices invoking the first names of Mars.

Mars in literature

The history of Mars and its associations with Earth is also a story of books. Not surprisingly, they are fascinating, strange books that we never tire of reading. Books by well-known and little-known authors. Works that are already part of the literary canon, as well as books that aren’t on the radar: hidden gems of the creative imagination. Books about Mars can date from ancient times while immersing us in the deep future and ungraspable present. There are jewels such as the Almagest, a highly prized incunabula written by Claudius Ptolemy in the second century AD. It is the major treatise about the geocentric cosmos that dominated Europe’s intellectual landscape for 1,300 years. Martian literature has also rediscovered Lucian of Samosata and his true stories, including the trip to the Moon he imagined satirising the intellectuals of his day, which some consider to be one of the first books in the protohistory of science fiction.

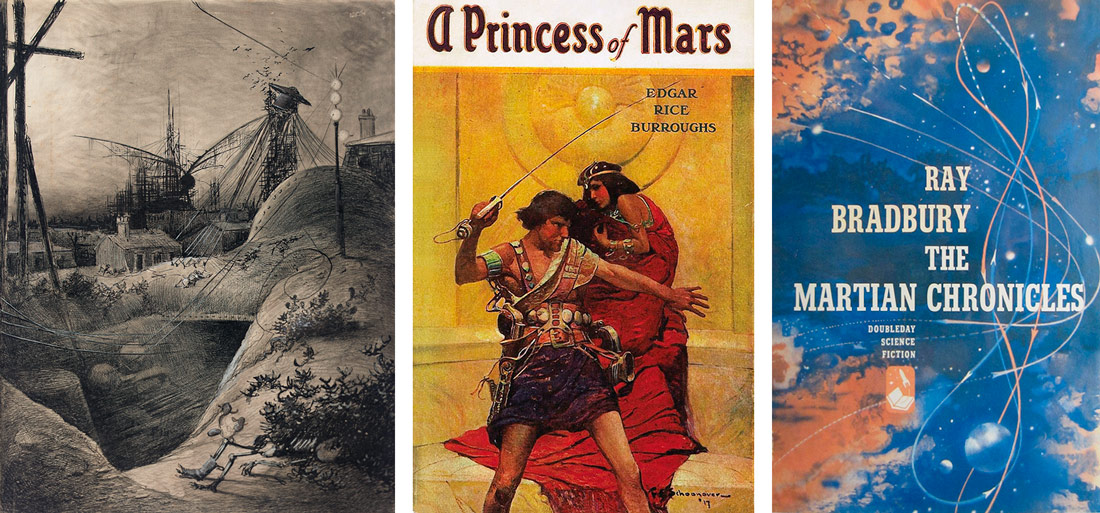

Books about Mars are heterodox. There is room for every genre and indefinable works. Books that are leaps into another dimension. Secret passageways. Illuminated pages to explain everything we have seen, imagined and projected onto the Red Planet. From Homer’s Iliad to Dan Simmons’ Ilium, from Johannes Kepler’s Somnium to the first edition of Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles, from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels that foretold the existence of the satellites of Mars, Phobos and Deimos, to H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, illustrated by Alvim Correa and which, decades later, Orson Welles turned into one of the most famous examples of fake news in modern broadcasting. We call them books, but they are also doors. They are all open and there is one, or there are several of them, waiting for you on the other side of the red mirror.

Dead London, illustration by Henrique Alvim-Correa for the French edition of The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells (1906). / Front cover of A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs (1917). / Front cover of The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury (1950).

Dead London, illustration by Henrique Alvim-Correa for the French edition of The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells (1906). / Front cover of A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs (1917). / Front cover of The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury (1950).

Feminist Mars

Science fiction about Mars written by women is one of the least known and least explored sides of the imagery associated with the Red Planet. And it has its own line of descent. In the 18th century, Marie-Anne de Roumier Robert wrote Voyages imaginaires merveilleux, a fantastic voyage through the solar system, which is considered one of the earliest examples of feminist science fiction. In the late 19th century, the American authors Alice Ilgenfritz Jones and Ella Merchant published Unveiling a Parallel. A Romance: a novel in which the Martian civilisations of Paleveria and Caskia serve to reflect on the relationships between men and women in the context of their time. In the early 20th century, the Australian writer and activist Mary Ann Moore-Bentley also resorted to science fiction to condemn existing injustices and inequalities. Every feminist wave is reflected in the evolution of the genre, while the influence of Martian imagery in the popular culture of the last century is becoming essential, myth-busting reading. In this podcast, the critic and researcher Elisa McCausland conflates the relationship between Mars, feminism and pop culture from the 1950s to the present day.

The Utopian laboratory

Enduring works have stories of love, passion and perseverance behind them. Their creation requires a guiding vision and a sustained determination willing to adapt to every circumstance. Kim Stanley Robinson has summarised all the years he has spent creating his famous Martian Trilogy in a glossary of ten terms that you’ll be able to discover when you visit the exhibition, but here’s a preview: The Utopian laboratory. A definition that can’t be bettered, in which the act of writing coexists with changes of residence, raising children, difficult work schedules and work-life balance. Because, as Robinson warns, imagining a better world means including everybody. Utopia is for everybody, otherwise it is nothing.

Mars

The Red Mirror

25 February — 11 July 2021

This exhibition looks at our relationship with Mars, from antiquity to the present day. Science, art and literature come together in a major exhibition project that coincides in time with the arrival of three space missions to the Red Planet. Mars. The Red Mirror explores our condition and future as a species and the ultimate nature of the universe we live in.