Inside the exhibition

A Tosquelles Glossary

This “Inside the exhibition” section invites you to discover the fascinating personality of Francesc Tosquelles and his transformative practice through ten key concepts. His practice not only responded to therapeutic needs but to cultural and political ones too, in a process that involved and transformed the care institution itself.

The concepts that make up this Tosquelles glossary (which is, necessarily, incomplete) are Art brut, therapeutic community, nonsense, extermination douce, the cassette method, hypocritical method, Little Vienna, institutional psychotherapy, the pictures on the wall and sectorialisation. The ten concepts have been proposed by Carles Guerra and Joana Masó, the joint curators of the exhibition Francesc Tosquelles. Like a Sewing Machine in a Wheat Field, and have been brought to life through illustrations by Oriol Malet created specially for this glossary.

Texts by Carles Guerra and Joana Masó, illustrations by Oriol Malet.

Art brut

In the 1940s, the artist Jean Dubuffet coined the term art brut to refer to works of art made by people outside the artistic mainstream. It is often said that psychiatric institutions are one of the places where art brut originated, but it only existed when these objects and works were taken outside the hospitals and Dubuffet transformed them into works to be collected. Dubuffet’s projects differed profoundly from Tosquelles’. Far from being fascinated by the anticultural stances that interested Dubuffet, Tosquelles had made cultural practices into a tool to establish the social links that classical psychiatry had denied the patients.

Therapeutic community

During the Spanish Civil War, Tosquelles worked in therapeutic communities that preceded the ones established in England in the 1950s. The entire medical community, inpatients and non-professional teams, who were part of civil society, were involved in the healing process. In the different places where he worked, Tosquelles collaborated with musicians, writers, sex workers and painters to bring about a more collective, less-specialised relationship with the treatment of the illness. Tosquelles said that he had been influenced by the therapeutic communities avant la lettre that Lange had set up during the First World War.

Nonsense

When describing psychiatry, Tosquelles always cultivated a way of speaking marked by a dry sense of humour that invited people to listen and empathise. He often resorted to talking nonsense as a way of experimenting. He thought that, by doing so, people may actually be able to say something. Over the years, this ambulation through the word began to distance Tosquelles from the privileged relationship Lacanian psychoanalysis had with meaning. It was then that he gradually began to move closer to the material of the voice and sound, of music and the cadence of language at the point of healing.

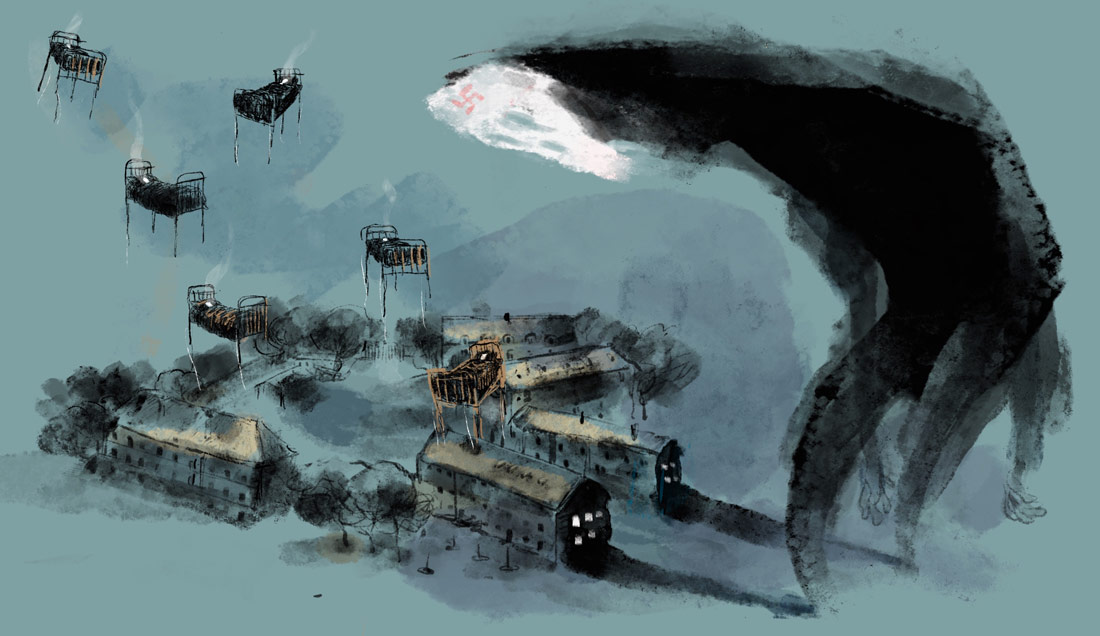

Extermination douce

More than 40,000 patients died in psychiatric institutions in Vichy France in the early 1940s. In L'Extermination douce, Max Lafont attests to a period marked by suffering, by what Lucien Bonnafé referred to as a "concentration-camp disease". The institutions where the inpatients were fed a deficient diet were ravaged by hunger. Meanwhile, Nazi Germany was implementing Aktion T4, a secret plan to exterminate mentally ill patients. It doesn’t take much to see that, in France, this slaughter was the product of a deliberate policy, rather than a chance occurrence. Tosquelles arrived in Saint-Alban at the precise moment when death was prevalent in all the institutions in the country.

The cassette method

This method, or procedure, originated as a means of collective supervision with a group of younger doctors at the Institut Pere Mata in Reus in the late 1960s. It gradually became an almost liturgical method of meetings held twice a week with five groups. Each group had a secretary, and the sessions were held outside working hours. Tosquelles didn’t write much about this device. Other participants remember it as a countertransferential mechanism where people discussed medical cases in an impromptu and informal manner. Others noted their intensity and anguish. Now, almost a thousand cassettes hold the recordings of these exchanges that are subject to medical secrecy.

Hypocritical method

Tosquelles’ personal album contains two photomontages. Everything about them suggests that they were taken in 1944 by a photographer called Jacques Matarasso. Using a photograph of Tosquelles having an afternoon nap with his feet in the foreground, the image is reversed and a tiny figure has been placed inside. It is Tosquelles holding a fishing rod and approaching the soles of his feet to read them. Below it, we read La mèthode hypocritique I and II. No texts have been found to explain what it means, except for a few statements in which Tosquelles suggests that a principle of knowledge can be found in the soles of the feet, which is triggered when we stand up and walk.

Little Vienna

Following the proclamation of the Second Republic in 1931, Barcelona welcomed many psychiatrists from Freud’s circle who were fleeing Central Europe. The rise of Nazism was driving them into exile. Tosquelles was psychoanalysed by one of them, Sandor Eiminder. The experience marked him for the rest of his life and led him to consider foreignness as an inherent condition of psychoanalytical work. This is why Tosquelles always remembered Little Vienna as the time when Barcelona had spontaneously become the intersection between psychoanalysis and Marxism. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War put an end to this period.

Institutional psychotherapy

Institutional psychotherapy was the term coined by the psychiatrists Georges Daumézon and Philippe Koechlin in 1952 to refer to a series of therapeutic practices being carried out at the hospital in Saint-Alban where Tosquelles had been working since 1940. To cure the inpatients, this way of practising psychotherapy involved transforming the entire psychiatric institution, conceived as a series of links (between doctors, nurses, nuns and farmers) and material relationships (the self-managed structure of the different wards, parties and theatre plays, and the ergotherapy workshops through a cooperative economy).

The pictures on the wall

Tosquelles said that he had spoken to Michel Foucault in the late 1960s. It would appear that, immediately afterwards, he drew two diagrams on cardboard. One referred to attitudes towards madness and the other to madness as a human phenomenon. These lists of authors and concepts can be read as if we were moving forward slowly inside a body with entrances and exits, while going through a process of digesting history and institutional practice. Tosquelles’ writing obsessively fills the nooks and crannies and circuits of this organism. When he explained their meaning at the training sessions with the carers and medical staff at the Institut Pere Mata, laughter was always guaranteed.

Sectorialisation

In the 1960s, a sectorial psychiatry was developed in France. It advocated curing patients outside the walls of psychiatric hospitals. For Tosquelles, this sectorialisation had begun years earlier with the Catalan Commonwealth, the Mancomunitat, and Republic. This was a time when rural workers had a real influence on production relations. Voluntary work schemes for patients in the region were also introduced as a way of integrating them into society. During the transition, Tosquelles was also involved in setting up the children’s collectives with special-needs educators. They decentralised the three main municipal charitable children’s homes where 600 children were living. They made sectorialisation a reality in different neighbourhoods with self-managed life groups.

Francesc Tosquelles

Like a Sewing Machine in a Wheat Field

8 April — 28 August 2022

The exhibition takes a look at the avant-garde practices that the psychiatrist Francesc Tosquelles carried out in the therapeutic, political and cultural field. Tosquelles transformed psychiatric institutions during the Republic and in fascist Europe. Today, he is an inspiration when addressing mental health policies in times of extreme crisis.