Inside the exhibition

Unmasking “The Mask Never Lies”

In this “Inside the Exhibition”, we wanted to remove the mask from our exhibition project and focus on some aspects, themes and details that visitors will not find while walking through the physical space of the exhibition.

Any exhibition that is open to the public is essentially a mask that hides the scars of a long process of collective work. It is also the final image resulting from an intricate selection and decision-making process that often means that some things found along the way do not make it into the final assembly. Therefore, let us think of this text as the extra content menu in one of those DVDs that today have unfortunately become obsolete: excerpts from interviews that were cut, but that shed light on details and sub-topics that could never have appeared in The Mask Never Lies: The Making Of, some artistic productions made especially for the show, jewellery that did not fit in the final space, references and memories throbbing behind some of the presences of the exhibition. In short, a show of polymorphic and mutant varieties, worthy of a cabaret as spectral as the Voltaire, the cradle of Dadaism.

A text by Jordi Costa, co-curator of the exhibition.

- A dark brotherhood

- The immortality of the man of a thousand faces

- Two sorceresses compress time

- Returning to the Cabaret Voltaire, 40 years later

- Colonial métissage

- From the balaclava to the hood

- Touch in times of apocalypse

A dark brotherhood

The connections between the Ku Klux Klan and other fraternities

There are many underground currents in The Mask Never Lies that connect some of the various areas of the exhibition. One of them is about secret societies and their close relatives: fraternities and discreet (and not necessarily secret) circles that are sometimes vulnerable to slander or black legend. The Ku Klux Klan emerged in a context that could connect it both with groups of vigilantes trying to impose their own law on a chaotic land (another leitmotif of the exhibition is the connection of this idea of the superhero’s identity and ambiguity) and with a world of fraternities that were governed by their own codes and were an essential part of social life throughout the 19th century. In this unpublished excerpt from the interview with Elaine Frantz Parsons, author of the book Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan during Reconstruction and a true inspiring voice in the “Wild Carnival” section, the academic clarifies the similarities and differences between the first Ku Klux Klan and other organisations such as the Freemasons, the Odd Fellows and the Knights of Pythias.

The immortality of the man of a thousand faces

Fantomas, the source of inspiration for surrealism

Fantomas, the character created by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, and brought to the cinema for the first time by Louis Feuillade, even managed to escape its creators’ control to infiltrate the imagination of many other artists. One of the most fruitful relationships in the character’s escape was the one that the man of a thousand faces established with the surrealist René Magritte, who would treat him almost as a perverse alter ego and a symbolic incarnation of death. For the surrealist movement, Fantomas embodied the anticipation of his (a)moral, political, and aesthetic programme, and to some extent the series that Feuillade dedicated to him was read by its members as a draft on the possibilities of surrealist cinema due to its ability to re-enchant everyday spaces through imagination and for its power to forge images that may have seemed prosaic, but always contained potential for suspicion.

The short film Monsieur Fantômas (1937) was the only film directed by the Belgian surrealist poet Ernst Moerman who had published the book of poems Fantômas 1933 four years earlier, dedicated to Jean Cocteau. A work lying outside the canon of surrealist cinema, the film proposes an interesting dreamlike exploration of the link that united Magritte with Allain and Souvestre’s creation: the same artist appears painting his painting Le Viol, in a scene that seems to evoke the space of the wall that bleeds in the episode “Fantomas versus Fantomas” from the Feuillade series. At another point in the short film, the discovery of a female corpse on the beach is as a direct nod to L’Assasin menacé, one of Magritte’s works most directly connected to Feuillade’s imaginary. But the reference of the approach points to several groups, and Moerman manages to represent what Feuillade had not dared to bring to the screen (but that Allain and Souvestre had proposed in one of their novels): the character’s transgendered transformation, who here adopts the personality of a nun. “I keep the obsessive and blurry memory of reading Fantômas, of what we might consider a dream, an epic poem, more unreal than absurd, set in a world where nothing is impossible and where a miracle is the shortest path to our inclination to mystery. Working with the script of Monsieur Fantômas, I have tried to create a communication with that world, in which a fantastic reality reigns, making each object, each visible thing, shine with its own real and inner light”, wrote Moerman. The film also included quotes from Moerman’s friend Paul Éluard and slapstick appropriations. Curiously, the one who plays Fantômas in Moerman’s play is Léon Smet, the father of future French rock idol Johnny Hallyday.

In the King of the Ghosts section, the exhibition The Mask Never Lies speaks of Fantomas in the context of Paris at the beginning of the century where an upsurge in crime came head-to-head with the new tools of control of the forensic police. Moerman’s short film serves here as the missing link between that chaotic moment and the dreamlike reinterpretation of those tensions between law and desire that Magritte and other members of the surrealist movement would propose.

Two sorceresses compress time

Mary Wigman and Emmy Hennings, avant-garde artists, witches and sorceresses

From the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich to the Monte Verità naturist community, Emmy Hennings and Mary Wigman cast their artistic spells to exorcise the hell that summoned the tragedy of the First World War, an apocalypse where new forms of masked faced emerged (the dehumanising gas masks and the broken faces mutilated in the war), which seemed to demand a recovery of the magical and transformative virtues of the mask to re-enchant the world. Hennings and Wigman are the protagonists of two graphic novels drawn respectively by José Lázaro and Joaquín Santiago García, with both scripted by Fernando González Viñas: El ángel dadá (“The Dada Angel”) and Mary Wigman: danzad, danzad, malditos (“Mary Wigman: Dance, Dance, Cursed Ones”) (publication forthcoming in 2022). The three artists participate in the exhibition with original material from these works (illustrated scripts, definitive plans), but also with two imposing murals produced especially for it, which establish a complex dialogue through the compositional use of a mirror. In this video made with the time lapse technique, we have the privilege of witnessing the simultaneous creation of the two pieces, as if Hennings and Wigman, two artists who exemplify the merge between the avant-garde artist and the witch and the sorceress, had cast a spell to compress time. One of the references borne in mine when designing the The Spectral Cabaret section was the version of Suspiria made by Luca Guadagnino in 2018, which explores the idea of a magical counter-power embodied in artists in which the keys of expressionist dance resonate.

Returning to the Cabaret Voltaire, 40 years later

An alternative history of the origins of Dadaism

All the artistic productions made especially for The Mask Never Lies contain a story, but perhaps Cabaret Voltaire, by Martí and Onliyú, is the one that carries the greatest weight on its shoulders. In the issue no. 11 of the magazine El Víbora, the authors began their cultured and wonderful series The Contemporary Age with the nine-page history “Zürich 1916”, offering an alternative story of the origins of Dadaism with Lenin and the spy Mata Hari in the background.

Zürich 1916 by Martí and Onliyú, published in issue 11 of the magazine El VíboraA reproduction of the cartoon (1980). Courtesy of Ediciones La Cúpula

Zürich 1916 by Martí and Onliyú, published in issue 11 of the magazine El VíboraA reproduction of the cartoon (1980). Courtesy of Ediciones La Cúpula

Everything that has to do with Dada and the evenings at the Cabaret Voltaire is fragile and volatile: in fact, the original painting Cabaret Voltaire by Marcel Jancó is a lost work that the author revived years later in the form of a lithograph. For The Mask Never Lies, we thought of another way to resurrect the missing oil painting: by commissioning the authors of “Zürich 1916” to create a reinterpretation that would in fact allow them to return to the legendary Cabaret Voltaire 40 years later. Their perspective as underground survivors bestows the symbolic weight of an allegory about the human tragedy of the Battle of the Somme to the skeleton presiding over the stage where Tristan Tzara speaks with Hugo Ball dressed in his finery of a magic bishop, surrounded by an audience that transmutes itself under the formal inspiration of Marcel Jancó’s masks.

Cabaret VoltaireMartí and Onliyú (2021)

Cabaret VoltaireMartí and Onliyú (2021)

Colonial métissage

The Mexican mask in times of colonial domination

In the The Struggle section, the exhibition summarises Mexican culture by focusing on the mask in a timeline that opens with the military ranks of the Aztec warriors, passes through the ramifications of wrestling in popular culture and social activism, and culminates in the Zapatista movement led by the charismatic and elusive Subcomandante Marcos. However, this story leaves out many meanings of Mexican masks, meanings that include universes, such as the many masked celebrations that took place over the 300 years of colonial rule and often use false identity as the critical tool against power. Mauricio José Schwartz, the author of the book Todos somos Superbarrio, (“We Are All Superbarrio”) brings some of these rituals to light in this unpublished interview excerpt.

From the balaclava to the hood

From Pussy Riot to the new feminisms of Latin America

The exhibition also traces a labyrinthine path of echoes, resonance and legacies, weaving a framework where the dialogue of a comic strip can be transformed into a political slogan (or vice versa). After the trial of the members of Pussy Riot, their multicoloured balaclavas could no longer protect their identity, but instead became a symbol of protest amplified by the seductive power of the language of fashion. Their energy did not go away: over time, Pussy Riot balaclavas found an unexpected but consequent legacy in hoods, which would become a hallmark of feminist struggles in Chile in 2020, before their spread throughout Latin America. Hoods entered dialogue with the traditions of indigenous crafts, exploded and diversified into forms of queer identity and ultimately turned the experience and biography of those who made and wore them into pure form and colour. The “Forbidden to Disappear” section culminates with the work of artists who have promoted very radical takes on the phenomenon, such the work of Las Migras de Abya Yala (Jahel Guerra and Lorena Álvarez) and the work of the Colombian May Pulgarín, also known by the nickname Tropidelia.

Touch in times of apocalypse

References and layers of meaning in the piece T(ouch)! by Antoni Hervàs

The installation T(ouch)! by Antoni Hervàs (made in cooperation with Gitano del Futuro and the audiovisual artist Beatriz Sánchez) brings a great festive climax to The Mask Never Lies. The exhibition was designed and scheduled before a pandemic forced us into confinement, but it was inevitable that our sudden dystopia would require thought on surgical masks and how they have conditioned our gaze, life and social and emotional relationships. In fact, the pandemic mask turns the very idea of the Carnival upside down, turning the covered face into the norm and the exposed face into disruption and a new source of anxiety and fear.

There are many references that the artist used when designing his installation, including such diverse and irreconcilable icons as the Latina diva Iris Chacón, the shock rock of Screaming Lord Sutch and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Mary Santpere from La “mini” tía, Grace Jones from Vamp, an ice show based on James Cameron’s Aliens and the iconic version of The Masque of the Red Death directed by Roger Corman with photography by Nicolas Roeg.

But let’s listen to the artist so he can reveal the various layers of his approach: “I was interested in all that British tradition of shock rock, where artists took on iconic horror characters. In his case, the recurring theme was serial killers, not so much the pandemic, but I thought this might be my way of approaching the issue of Covid. I wanted to talk about the desire for the forbidden, the inability to touch... This is what has been most affected by the pandemic. I don’t know what intuition led me to relate the shock rock tradition to Iris Chacón, with her enthusiastic but not necessarily graceful showmanship. When preparing the piece, in the end, what I wanted was the impossible: to organise a party at a time when it could not be done, a performance where people had to touch each other at a time when it was forbidden to do so. I also wanted to do it with Gitano del Futuro, who is an artist I have been following for a long time and who has always fascinated me when I saw him on stage: he is very elegant, but at the same time it all leads to terror, to sexy aggression. He was the ideal person to find this point of contact with the tradition of shock rock. The song he composed for the piece changes in style. At first, I asked him to do trap, because he comes from that scene, but he came in with electronics and then he added Catalan rumba with shock rock fusion, which drifted towards the more urban rhythms that, in principle, I had asked him for. It seems as if the song mutates at the same time as the virus: from Covid to the Delta variant and later to Omicron, in line with the shift from electronics to rumba and urban rhythms. I didn’t want to make a conventional video clip, and in this sense, Beatriz Sánchez’s work as the director was key. She added many layers to the project and found the perfect register to show how we can feel attraction to what can kill us. The staging thus appropriates elements of an escape room. Finally, the sculpture in the music video alludes to shock rock props: those coffins from which the artists of the subgenre emerged, but in a version recalling Giger. The materials I used all refer to Covid: latex gloves, masks, press clippings alluding to the pandemic... During confinement, many people were engaged in making crafts with what they had by hand, and the piece tries to include all this”.

T(ouch)! Antoni Hervás GIF (2021)

T(ouch)! Antoni Hervás GIF (2021)The Mask Never Lies

15 December 2021 — 1 May 2022

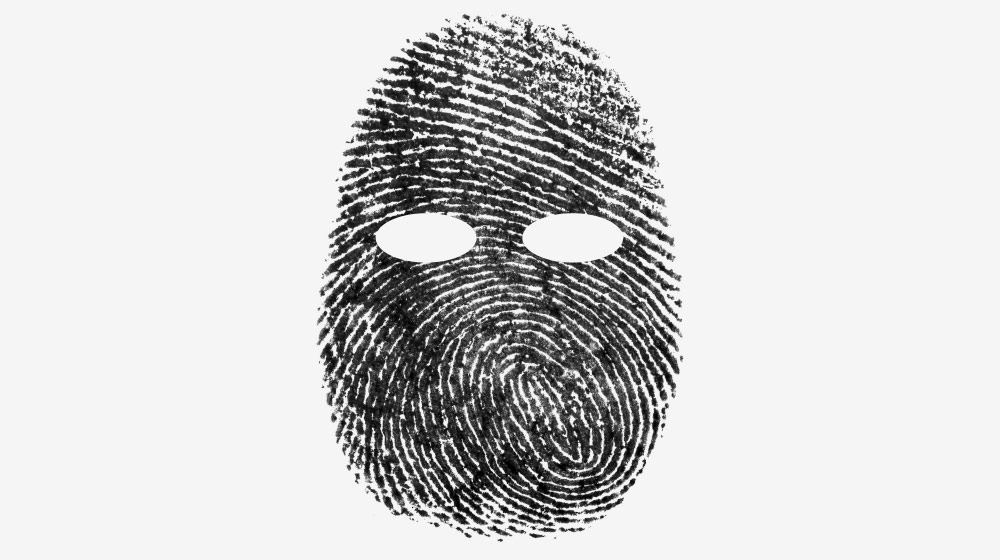

The Mask Never Lies takes us on a journey through the political uses of masks in modern society and looks at the politics of how faces are controlled, cultural resistance to identification, the defence of anonymity, the strategies of terror in the act of concealment, and the way in which bad guys, heroes or heroines and dissidents use masks as a symbol of identity. Our world cannot be understood without masks and maskers, and even less so nowadays, when a pandemic has forced us to live behind them.