Inside the exhibition

Thinking Like an Octopus

Several artists in the "Science Friction" exhibition tell us about their relationship with scientific knowledge and how they incorporate it into their creative strategies. Their voices, alongside other reference points in the exhibition, open up possible paths on the long journey of interaction between species.

A text by Maria Ptqk, curator of the exhibition.

It has three hearts, a short life span for an animal of this size and a complex nervous system, albeit very different to the human one. Clever and cunning, it has a remarkable learning capacity, but, unlike other so-called smart animals, it prefers living in solitude. Every day, science brings us new data on the extraordinary existence of the octopus, data that challenge our ideas about what it means to think or feel.

In those points of friction where biology and philosophy inspire one another, both advancing somewhat haphazardly, art plays a key role. Linking disciplines, translating between languages accustomed to not being understood, its methodless method, embracing the process and experimentation, makes it a fertile testing ground to imagine those other forms of life that, like that of the octopus, we can barely manage to conceive.

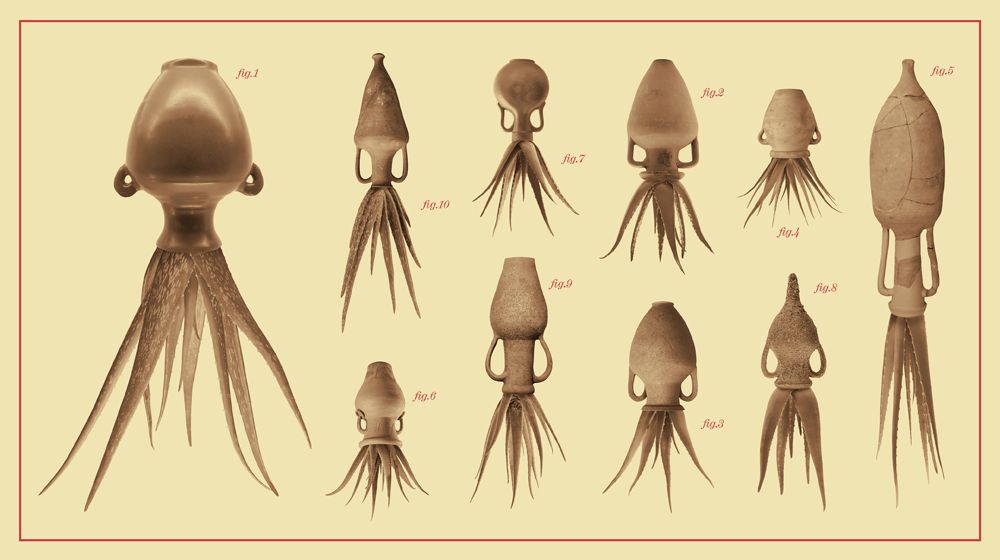

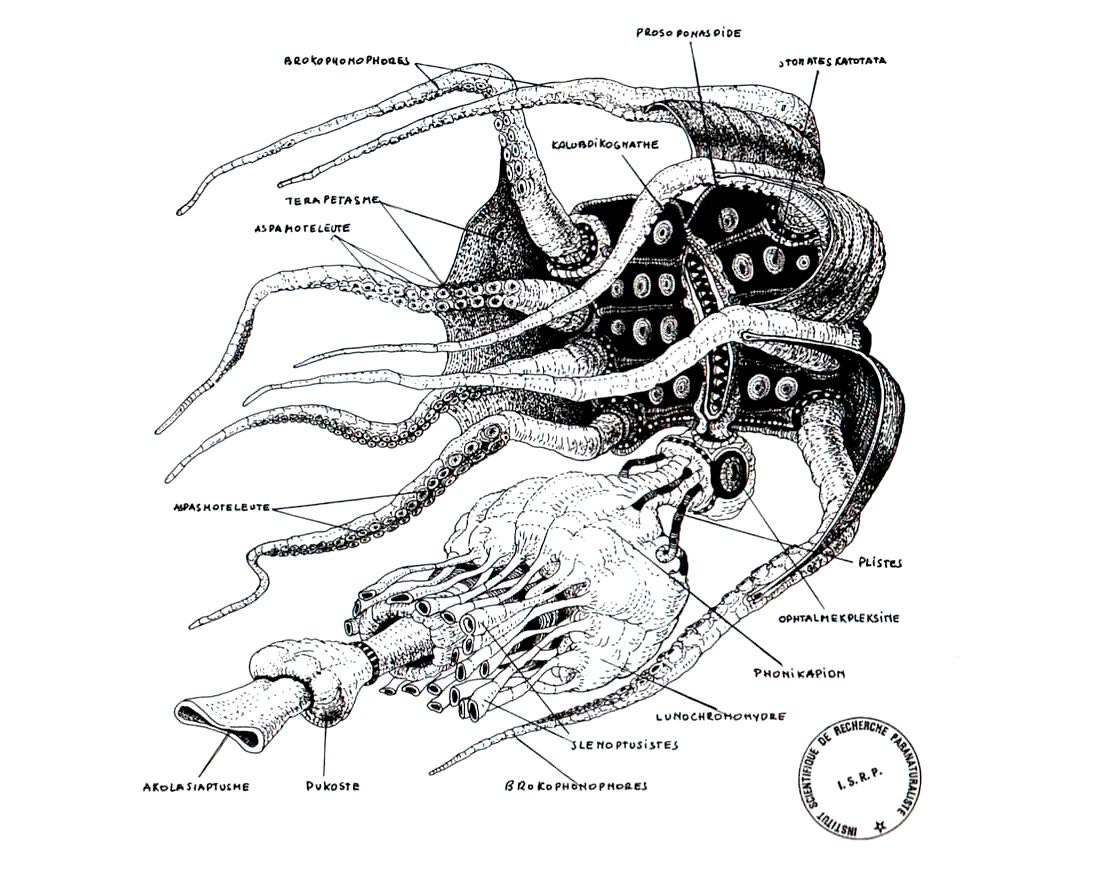

Lumanter Phusagrion specimen, 1988, Vilém Flusser and Louis Bec, Vampyroteuthis Infernalis: A Treatise, with a Report from the Institut Scientifique de Recherche ParanaturalisteLouis Bec, , University of Minnesota Press, 2021.

Lumanter Phusagrion specimen, 1988, Vilém Flusser and Louis Bec, Vampyroteuthis Infernalis: A Treatise, with a Report from the Institut Scientifique de Recherche ParanaturalisteLouis Bec, , University of Minnesota Press, 2021.

Knowing through the body

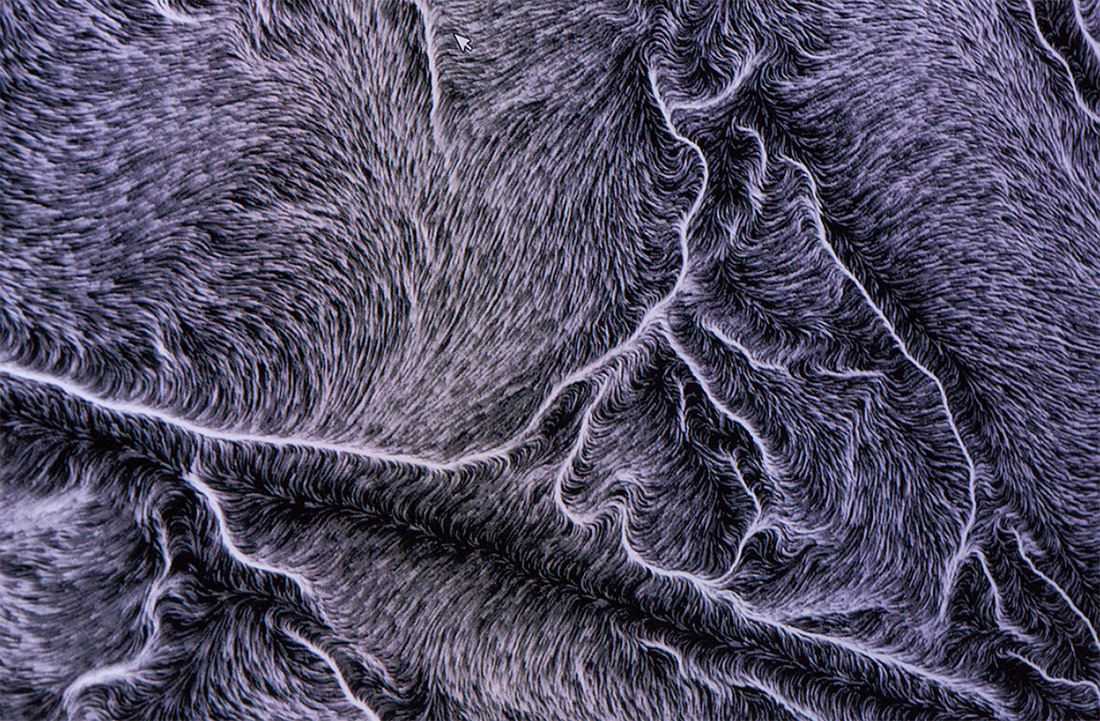

It is not yet clear whether what the octopus skin does when it changes colour (green, blue, grey, yellow, ochre, orange...) is a manifestation of what is happening inside its body, a reflection of what is happening outside its body or something else entirely. Is it a skin-antenna, a skin-screen, a seeing skin, a skin connected to its brain’s neurons or to the neurons of its tentacles, home to the majority of its neurons? In the story Autobiography of an Octopus by Vinciane Despret, the symbiote Ulysses tries to explain to the scientist what they have come to observe, calling it “carnal suggestions”.

Those in the field of neurology studying how the connection between body and mind works contend that, when a person draws, the hands do not simply carry out the brain’s orders, but, in an inexplicable manner, actually think. In the concentration that takes place in the painstaking observation of something with a view to sketching it, or in the endeavour to convey abstract ideas through drawing, observation is said to merge with motion, and recording with understanding. The combined action of the hands and the brain creates something that neither the hands nor the brain can do on their own.

It is perhaps one of the reasons why even today, in the age of pixels, scientific illustration continues to be imperative for the study of living beings. Zoologists, entomologists and botanists make use of drawing, rather than photography or video, to capture the exact colour of a leaf or wing vein. Capture, not only in the sense of expressing but also of understanding.

From Alexander von Humboldt or Charles Darwin to Francis Hallé, it is true to say that the great naturalists have often been skilled draftspeople. Maria Sibylla Merian understood the relationship between insects and flowers by virtue of drawing them, just as, much later, Ernst Haeckel obsessively engaged in making illustrations of radiolaria before concluding that the complexity of life could not be related without coining a new word: Ökologie. The coral drawings and crocheted reefs made by Petra Maitz like the sculptural paintings made by Susana Talayero, herself inspired by Merian, convey this kind of thinking-doing. Despite being linked to science in a different way, both merge movements, sensations, mental connections and, needless to say, materials (graphite, ink, paper or textile, with their vegetable, mineral or animal origin) to produce something that is not the mere execution of a technique.

Feeling in a network

One of the most puzzling aspects of octopus biology is that its nervous system is not centralised in a main organ, like that of humans, but is spread between the brain and its eight tentacles, where the majority of its neurons are located. The tentacles, besides having a sense of touch and taste, show autonomy and the capacity to make decisions. According to cephalopod expert Peter Godfrey-Smith to understand the mind of the octopus you have to imagine it like a jazz orchestra: sometimes the musicians (the tentacles) pull together to play (under the direction of a head conductor), but other times they go their separate ways, improvise and perform their own melodies, beyond the main melody. In his opinion, octopuses live outside the common body-brain divide.

It is difficult for us to conceive an animal whose brain and body run on a decentralised nervous system, but nature is home to many organisms that live life in a network. Plants and fungi are the best known, but also insects considered superorganisms, such as bees or ants. “We are all lichens”, claims biologist Scott Gilbert to express the idea that, from a strictly biological point of view, there is no such thing as an individual. Instead, we are symbiotic ecosystems, an assemblage of a multitude of different forms of life (we too, with our 200 microbial genes for each human gene, are actually giant colonies of bacteria). Lynn Margulis coined the term holobiont for this unit.

In Holobiont Society, Dominique Koch wonders about the implications of this scientific evidence. What does politics or society mean if the human body is nothing but a cluster of microorganisms? In no man’s land where words fail, image and sound editing produce meaning in another way. Through folds and overlays, scales (micro, macro and meta) blend with one another in an uncertain and generative humus. Inspired by Haraway’s work, Koch creates an unstable experience, a place inhabited by problems not answers.

MyconnectSaša Spačal, Tadej Droljc, Mirjan Švagelj and Anil Podgornik, , 2021.

MyconnectSaša Spačal, Tadej Droljc, Mirjan Švagelj and Anil Podgornik, , 2021.

“We don’t know how a mushroom thinks”, asserts Saša Spačal about the human-mushroom translation interface Myconnect, “but technological experimentation can bring us closer to it, expanding our capacity for perception towards non-humans”. Here too, technology joins forces with speculation to imagine interspecies communication facilitated by electrical signals. If all living things are sensitive to electricity, could we invent a language to connect through it? Could we thus perceive something similar to what a networked organism feels? This frontier language, continuing with the science friction exercise, could be called OpisthoKont, the name of the group of eukaryotes from which we humans and fungi originate, our last common ancestor.

Dehumanised being

The new terrestrial habitation that seeks to re-establish contact with our non-human companions needs this kind of impure composting. Trial and error exercises, radical, transdisciplinary and undisciplined research, experiments that cannot be carried out in laboratories because their questions are not considered relevant, strange ideas for science that are making inroads in the realm of artistic creation.

Trans*Plant, the chlorophyll transfusion experiment developed by Quimera rosa, was not performed in a laboratory either. Following extensive research, it was taken on by the Kapelica gallery, specialised in bioart. In the words of its creators, Trans*Plant extends its research on the issue of identity: first around sex-gender categories and now on the taxonomies that separate some species from others. Both cases play with sorting the world in which it is not clear where science ends and the management of living things begins. Ernesto Casero also joins that slippery terrain with his fake posthuman protests. The result, skirting the border between absurd and ironic, shows the extent to which we need to renew the languages of the political imagination if we wish to make room for other forms of sensibility, subjectivity or intelligence.

Interestingly, Casero’s fake protests are not so far removed from those proposed by researchers from the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology with Octopi Wall Street. Sprinkled with humour, to tease invertebrate geeks, the poster is a strong critique of the anthropocentrism that underlies the taxonomies of the natural world. Because, if 97% of animals are invertebrates, how can the imaginary about the animal world be so overwhelmingly dominated by vertebrates? What vying for identity is concealed behind this “taxonomic greed”?

What would a non-anthropocentric taxonomy be like? A taxonomy governed, for example, by the genus Octopus, with its more than 170 species, as superior intelligence? To this end, it should be borne in mind that the octopus’s mind is the result of an evolutionary path distinct to the human one, whose bifurcation took place 600 million years ago. To think like an octopus would then be to retell the story of life from that last point of contact, with decentralised intelligence being dominant and centralised intelligence being subsidiary or anecdotal. The octopod as king of the cephalopods, together with its nautilus siblings, cuttlefish and squid, descendants of its cousins-ancestors the molluscs, separated from that other distant branch of the family that gave rise to a few vertebrates.

Admittedly, taxonomy is a hectic battlefield within biology, in which each major discovery generates disputes and negotiations. Scientific arguments, philosophical controversies, power struggles (zoologists versus botanists, microbiologists versus everyone) and large doses of speculation intersect therein. If it is already hard to think like an octopus or to write the history of life with cephalopods as the main narrative, it takes a great deal of imagination to approach the next frontier in understanding intelligence: that of beings who are even devoid of a brain. Like the blob, whose nickname comes from a 1958 film starring a terrifying alien amoeba-like creature. The real blob, the terrestrial one, is Physarum polycephalum: a unicellular organism – that is, made up of a single cell – currently located in the myxomycete group (literally, slime mould) in the kingdom Protista, which is precisely the “catch-all taxon” (that’s what it’s called in taxonomic jargon!) created for eukaryotes that are neither exactly animal, nor exactly fungus, nor exactly plant. With its texture between slime and mould, the blob does not have neurons, but is capable of memorising its way through a maze. Its study, in which several disciplines converge, is pure science friction: an experimental terrain that destroys all certainties about the very idea of thought.

Physarum polycephalum, aka blob.

Physarum polycephalum, aka blob.

One last note on the word think that gives this text its title, a nod to Vinciane Despret’s essay Penser comme un rat [Thinking Like a Rat] (2009). Despret tells us that keeping the title was an act of resistance against the pressure of her colleagues to specify the meaning of the word think or, failing that, to eliminate the conjunction like implying a comparison between the thinking of rats and that of humans. For that, she clung to that title to hold onto the “discomfort” felt by herself and the reader, to “make the difficulty posed by meanings that only partially overlap discernible”, because that lack of connection is precisely what puts both thought and imagination to work.

Science Friction

Living Among Companion Species

12 June — 28 November 2021

Is it possible to imagine other earthly stories? Can we conceive of other ways of living among different species? This exhibition explores these issues with the help of a selection of works of art and popular science. It proposes a change of mentality and sensitivity that questions the supremacy of the human species, opting for a view of the world understood as an ecosystem where all the planet’s species coexist.