Exhibition

Bamako '03. Contemporary African Photography

After the exhibition Africas: the artist and the city (2001), with its in-depth exploration of African contemporary creation in its many expressive registers, the CCCB presents Bamako 03. Contemporary African Photography, a further look at the creative vitality of a region which despite its geographical proximity continues, for us, to be an unknown quantity.

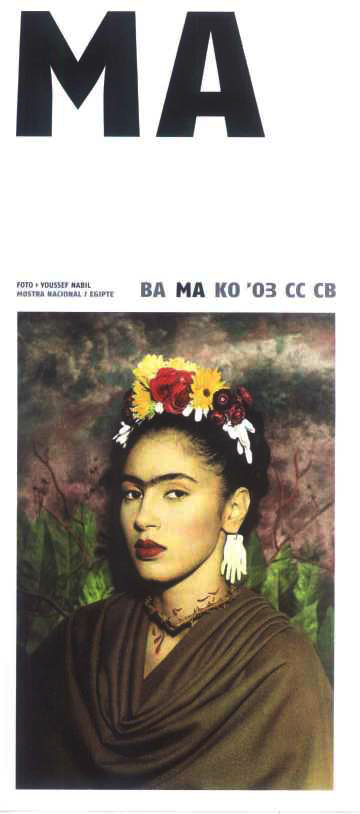

In this case, the project centres on the world of photography. We present in the region of 200 of the 2000 photographs that made up the last Rencontres de la Photographie Africaine de Bamako, a biennial event that, after five editions, has become consolidated as one of the continent's foremost artistic meeting places. This year's edition took place in the capital of Mali between 20 October and 20 November 2003 under the direction of Simon Njami.The exhibits on show at the Rencontres de la Photographie Africaine de Bamako and selected for presentation at the CCCB include the work of nine of the photographers who took part in the international show, last year with the theme of 'Sacred and profane rituals'. We also present a show of Egyptian photographs and the monographic shows devoted to Santu Mofokeng (South Africa), Youssef Safieddine (Lebanon/Senegal) and Van Leo (Egypt).

Thanks to an agreement with the organisers of Bamako's Rencontres (the Association Française d'Action Artistique - AFAA -- and the Ministry of Culture of Mali), the CCCB is able to present a broad-based selection of the latest show's most attractive proposals. The selection brought to Barcelona was made by Pep Subirós.

Curators: Josep Subirós (see Pep Subirós), Simon Njami

In the nineties, various publications and exhibitions were presented in Europe and the United States, presenting the non-specialised public with the extraordinary wealth of photographic creation in Africa.

The Rencontres de la Photographie Africaine in Bamako have played a major role in the 'discovery' of African photography. This biennial event organised for the first time in 1994 has since become consolidated as one of Africa's most important and interesting artistic meeting points.

The core of the biennial is constituted by a major international exhibition, pan-African in scope (including the diaspora), which last time round, between 20 October and 20 November 2003, turned around the theme of 'Sacred and profane rituals'.

The Rencontres also include a series of sections which, like the foremost film festivals, form a dense and varied mosaic that takes in personal approaches, heritage and tributes to great, recently deceased artists. With almost 2,000 photos presented, the Rencontres de Bamako offer a quality panorama of contemporary photographic creativity, at the same time providing a platform and sounding board for the exacting, rigorous, creative work that many artists carry out, day after day, in the most difficult conditions.

The contrast between the way the vast majority of Western photographers see Africa and the gaze of Africans themselves is particularly revealing. Unlike the former, the approach of African artists produces photographs that are often full of drama, but never sensational; full of singularity, but never exotic. They are gazes from the inside, often critical but always from the viewpoint of shared experience rather than condescending otherness.

At the same time, what the photos exhibited in Bamako manifest, almost without exception, is how, as Santu Mofokeng himself says in the introduction to his exhibition, the vast majority of African photographers are unsatisfied by beauty without truth.

Having said that, however, it is important to stress that Africa is immense, multiple, diverse and changing. The exhibition presented here does not set out to pontificate on the state of photography in Africa, but to present a view that is faithful to the spirit of the fifth Bamako Rencontres.

Given the impossibility of bringing all of the photos shown in Bamako, the idea is to present not a smaller scale version of all the participating photographers and all the exhibitions in the different sections, but complete expository series that maintain the unity and coherence of the projects presented. The exhibition at the CCCB therefore presents the work of nine of the photographers from the international exhibition, including those who won the main prizes, and the monographic show devoted to Santu Mofokeng, the Egyptian national show, Youssef Safieddine's work in 'Memories' and that of Van Leo in 'Tributes'.

1.- International show: Sacred and profane rituals. The divine irreverence of images

The general theme of the international show of the Rencontres de Bamako 2003 refers to the sense of ritual in our societies. Whether they are sacred or profane, rituals reveal the very essence of our humanity. Whereas sacred rituals are inhabited by God or by the gods, profane rituals relate to the individual. When applied to photography, they illustrate our relationships with the question of representation. The sacred is, by definition, that which we cannot see. That which we should not see. The profane, conversely, is common. The experience of everyday life.

Nonetheless, there are points at which the two experiences cross: the moment at which reality is transcended, transformed into something else. Something that explains our joys and our fears. Something that transforms banal reality into a spiritual experience. It is surely the mystery that Jean Baudrillard defined as 'the divine irreverence of images'.

Simon Njami

2.- Tribute to Van Leo (Egypt, 1921-2002). A simple repertory of desire

In a cosmopolitan Cairo that disappeared long ago, Van Leo was the photographer whom worldly society regarded most highly. Yet today, an overview of his work defies simplistic definitions. While Van Leo adopted characteristics that were obviously borrowed from Hollywood and its cult of the stars, his work went beyond the standard poses populating the postcards he collected as a child. Van Leo invented a genre of his own within studio photography, an avant-garde genre without precedent in the Arab world.

His portraits are icons that do not pretend to provide a faithful representation of reality; instead they negotiate the fabrication of an imagined personality with the realm of fantasy. By manipulating light, retouching the fine lines of a nose and spending hour upon hour in the dark room, Van Leo was able to transform a Spanish singer into Veronica Lake, a Ukrainian dancer into Elizabeth Taylor, an Egyptian housewife into Nathalie Wood.

For Van Leo, identity was never fixed, but completely malleable, a simple sign of desire, in view of the power of the medium that he had in his hands.

The selection presented here leaves out much of Van Leo's work, that which is best known to the public; the film stars, the dancers, the striptease artists and the beauty queens with their exaggerated poses are missing. Yet Van Leo managed to turn unknown, anonymous people into veritable characters.

These are not simple snaps, they are intimately framed studies that sometimes reveal the more nuanced textures of the face, like in a portrait of Hrant Kutnuyan produced in 1944. This portrait, as immediate and open as a landscape, also gives off a kind of evil eye, it is closed like a mask. Here, Van Leo gives us everything and nothing, the obvious and the hidden. On the back, the photographer wrote carefully 'a school friend'.

Negar Azimi

3.- Memories: Youssef Safieddine (Lebanon/Senegal). Art and colours

Senegal was one of the first destinations for the Lebanese who, at the end of the Ottoman Empire, fled from hunger and political tensions.

Youssef Safieddine forms part of that diaspora. In 1956 he opened Studio Safieddine in Dakar, in the tradition of Lebanese photography studios -- Étoile, Ali Baba, etc. Most of these studios' files have disappeared. The photographers gave their clients their portraits along with the corresponding glass plate or negative. Unwanted portraits were erased, and the glass plates, transparent once again, were sold in the markets.

Of Safieddine we have self-portraits playing the accordion, surrounded by friends or, all alone, imitating Tarzan, or accompanied by Fatmeh, his wife.

Art et Couleurs is a veritable storybook of the Safieddine couple in the 1960s. At that time of economic growth, hula-hoop parties and curled hairdos, the Beatles sang 'Love, Love Me Do'. Being in love was all the rage. The newspaper stands were invaded by photo-romances. Lyrical and rose-coloured, they presented kitsch shots of embracing couples, caught up by an eternal romantic love. The poses adopted by Youssef and Fatmeh are the same as those struck by the lovers in those magazines. Against a background of sunny landscapes, they gaze, smiling radiantly, at a joint horizon. The couple create a stage set for their complicity. On their trips into the country and holidays in Spain or Egypt, Youssef would set up the tripod and carefully frame the setting. His images go beyond narcissism to immortalise his family, professional and social success.

The portraits evolve. Black and white, montages, hand-coloured images, Kodak colour snaps, the links between Youssef and Fatmeh is unchanging. It resists the passing of time. Rather than a photo-romance, Art et Couleurs is a document of the history of two people in exile who have found new roots in their union.

Lara Baladi

4.- National show: Egypt. Reframing

Though Egypt may be a treasure for the photographic gaze, the country continues to have a fraught relationship with the lens. It is still difficult to take photographs there, as the sadly famous phrase mamnoua el taswir ('No photographs') is still omnipresent, as though this kind of representation should not be allowed to mere mortals. Similarly, taking a photograph of a person is still seen as exercising power over them.

Yet in the course of the second half of the 20th century, photography has helped to form local identities. You only have to go into an artisan's workshop or a café: the portrait of the proprietor, or more usually of his father or grandfather, takes pride of place.

Today, Egypt has changed century and the Egyptians have reappropriated photography for themselves in the context of an unprecedented change of paradigm. Photography has become a form of active participation and intervention, an escape from hegemonic visual constructions.

The selection of works presented here, produced with the help of a photographic or a video camera, testifies to the multiplicity of artistic languages and histories that Egypt now produces. By means of their rich pictorial inheritance, young photographers of the new generation will surely redefine the dominant visual codes and once again question the traditional aesthetic categories that have marked Egyptian society's relations with photography for so long.

Negar Azimi

5.- Monographic show: Santu Mofokeng (South Africa). Rethinking landscapes

'With this exhibition I take you on a journey in search of shadows, a search that informs my aesthetic. It would be easy to blame my parents for my obsession with meaning and purpose. And for the fact that I find no satisfaction in beauty without truth. Only I suspect the problem lies somewhere else, in the many manifestations of my consciousness, somewhere between 1956 and the present. I also have a vague idea about a part of me that I left out of my work for a long time: my spirituality! There are various reasons why I ignored it. One is a fear of the political and other implications, the ambivalence regarding my spirituality, some shame and, perhaps, the fact that my gaze is sidelong. This exploration is an attempt to accept my schizophrenic existence.

I grew up at a time of faith, a faith that was both ritual and spiritual. A rare cocktail of beliefs that includes pagan rites and Christian beliefs. And though I feel reticent to take part in this vaporous world, I identify with it. I would not call it 'peculiar'. As I have got older, I have tried not to get caught in the hypnotic embrace of faith, that seems to mock the self-confidence that I have so painstakingly cultivated. But I still feel ambivalent. I am ashamed of my shame.'

Santu Mofokeng