Inside the exhibition

Of Caves and Sybils

Five insights into William Kentridge

Here are five suggested paths to exploring the brilliant universe of the South African artist William Kentridge (Johannesburg, 1955). Kentridge is known for his drawings, films and theatre productions and for the impact his work, which mirrors the political and social changes in South Africa, has had around the world.

A text by Jordi Costa, head of exhibitions, CCCB.

More Sweetly Play the DanceWilliam Kentridge, , 2015, film still. Courtesy of the artist

More Sweetly Play the DanceWilliam Kentridge, , 2015, film still. Courtesy of the artist

Discussing Plato

Dancers, politicians, priests, typists, soldiers and sick patients dragging along their IV drips, form the seemingly endless procession that is the focus of William Kentridge’s installation More Sweetly Play the Dance. The work brings to an exultant climax one of the leitmotivs present in his animations, such as Shadow Procession, installations like The Refusal of Time and the tapestries in the Porter Series. Among the stream of heterogeneous characters, a group of individuals parades across the eight screens carrying images – faces, bath tubs, flowers, doves, typewriters – that seem to want to fix a series of (Platonic?) ideas in our consciousness. Inevitably, the viewer is transported at this point in the projection to one of the founding myths of Western culture: Plato’s myth of the cave, which, as Edgar Morin recalled in his essay “The Cinema, or the Imaginary Man”, may have been inspired by the shadow plays used in the mysterious forms of worship in Ancient Greece.

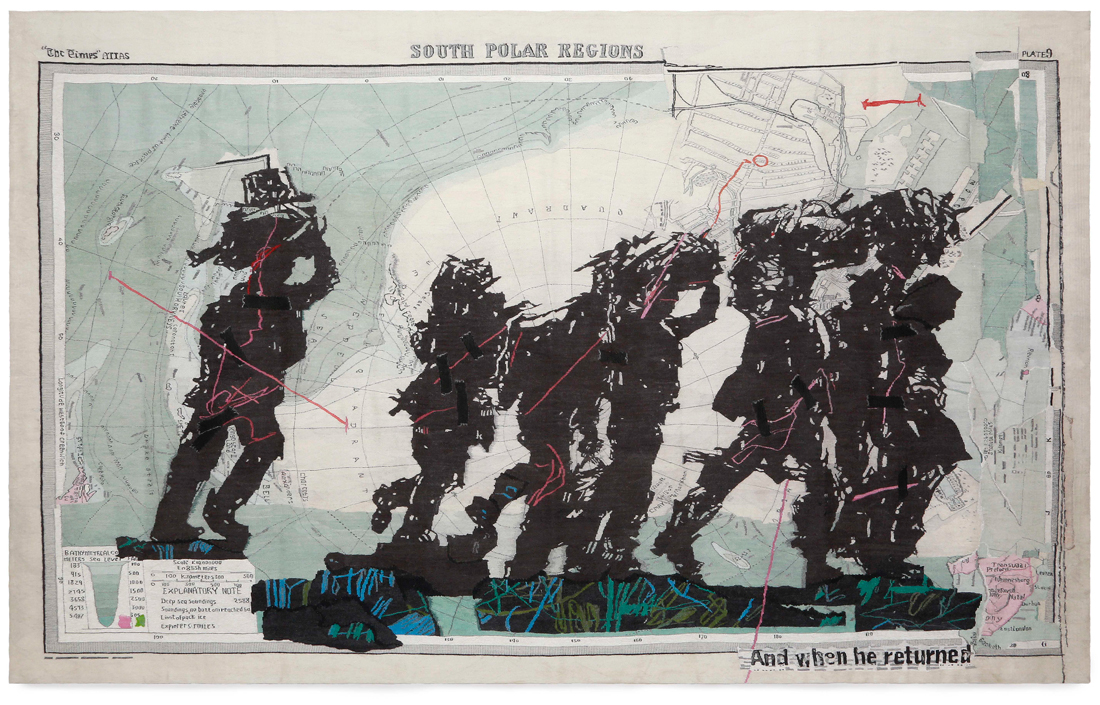

South Polar RegionsWilliam Kentridge, , 2016. The Stephens Tapestry Studio. Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

South Polar RegionsWilliam Kentridge, , 2016. The Stephens Tapestry Studio. Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

In the first of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures William Kentridge delivered at Harvard University, In Praise of Shadows, Plato’s myth becomes a discourse to be deconstructed. Kentridge corrects Plato by saying we should be sceptical about the light of knowledge that, according to the myth, frees the prisoners inside the cave who have mistaken the parade of shadows – that is, a performance – for tangible reality. The artist emphasises the fact that the light of knowledge is linked to power, which instrumentalises it and can use it to maintain a state of oppression or inequality. After all, colonialism was one of the corollaries of the culture of the Enlightenment. Among the shadows in the cave, and the light of knowledge that may have a hidden agenda, Kentridge proposes an intermediate space as the most fertile terrain from which to build his discourse. And here, perhaps, we might find the first key to approaching the work of the creator of the series Drawings for Projection: the vindication of the liminal space of doubt, ambiguity and uncertainty that will shake up the sterility of certainties.

The strange case of Soho Eckstein and Mr Teitlebaum

The ongoing series, Drawings for Projection, was begun in 1989 and currently features eleven animation films. It marked William Kentridge’s breakthrough on the contemporary art scene. To a great extent, the creation of these animations made from charcoal drawings ran in parallel to the gradual dismantling of apartheid – 1989 was the year Pieter Willem Botha stood down as the prime minister of South Africa –, the difficult (and far from achieved) task of building an equal society that has not yet erased the scars it bears on its body and in its memory. Kentridge has always been reluctant to consider Drawings for Projection as a chronicle or an illustration of apartheid, despite the fact that the landscape of Johannesburg – a territory that is as unstable as memory, or a trace that can be immediately rubbed out and transformed – provides the obvious backdrop to these pieces.

The mine owner Soho Eckstein and the poet Felix Teitlebaum are the two diametrically opposed characters that are central to the series. There may be an interesting mystery behind the way both characters have evolved as drawings during the thirty-year period in which the films have been produced; a stimulus for deciphering the meaning of the entire series and understanding why Kentridge doesn’t want to view Drawings for Projection as a story of apartheid. In the first film in the series, Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris (1989), Eckstein is depicted as a capitalist predator who could have emerged from a German Expressionist nightmare, while a naked Teitlebaum evokes the melancholic, disenchanted gaze of someone living on the margins, of a person outside his social class. In one scene, the characters fight each other, reminding us of Goya’s iconic Fight with Cudgels. Kentridge’s Drawings for Projection may not be a chronicle of apartheid, but it could be said that they closely resemble Goya’s Caprices and Follies conjugated in the particular time and space in Kentridge’s life. With every new film, Eckstein and Teitlebaum resemble each other more and more closely – in fact, they are both vying for the love of the same woman – and it isn’t long before we realise who they both look like: William Kentridge himself. Thus, what could be interpreted as a struggle between archetypal and stereotypical figures in the first films in the series shifts into a more complex tension: Eckstein and Teitlebaum as the dialectical split of the same person. Kentridge has sometimes talked about Eckstein and Teitlebaum as characters similar to those encountered in the Commedia dell’Arte, versatile tools at the service of a variety of ends. In this case, they are the emanations of the artist’s subjectivity that make it clear that the dominant feature of Drawings for Projection isn’t the historic event but the personal gaze of a contradictory individual – white, Jewish and privileged in an environment that rationalised and systematised inequalities – who has endured the cruelties of the time and place fate has condemned him to live in.

Poetics of transformation

In the third of his “Six Drawing Lessons”, Vertical Thinking: A Johannesburg Biography, Kentridge says: “The land is an unreliable witness. It is not that it effaces all history, but events must be excavated, sought after in traces, in half hidden clues. There is a similarity to the land and what it does, and our unreliable memory.” A city founded on mining, Johannesburg is bounded by an inhospitable landscape and unstable land: the artist remembers that, during his childhood, there were endless news reports – and urban myths – about houses or people who had been swallowed up by sink holes. Kentridge always insists that, in his case, it isn’t the mind that guides his hand, but the reverse: his art isn’t based on a preconceived plan from which a series of decisions are taken about materials and stylistic options. For him, it is the material that eventually leads to, and determines, meaning. In the case of Drawings for Projection, the traces of charcoal that can be erased, always leave a mark and are redrawn and transformed at the service of the unstable landscape of a Johannesburg that, according to Kentridge, is an animation in its own right: the malleability of the charcoal leads towards the ever-moving face of the city of Johannesburg and, from there, a logic of form leads to the theme of memory, full of empty spaces, and also unstable and unwilling to be fixed.

For Kentridge, life is a process, not a monolithic concept. According to the artist, you can see a table as an object or as the momentary stage in the life of a tree. Animation is the ideal language to give shape to this vision of the world: in an animation film, things are always moving – even the buildings and the asphalt, as seen in some of the pioneering works by the Fleischer brothers – and, therefore, this language of incessant transformation can act as the most faithful channel for the dynamic language of our subjectivity, our inner monologue, our desires and our dreams. Drawings for Projection feature a recurring character who triggers many imaginative visual metaphors: a black cat, who is the central figure in one of the spectacular tapestries on display at the exhibition William Kentridge: That Which Is Not Drawn. A cat that morphs into a bomb in Stereoscope, and into a telephone, a coffee pot, a gas mask and megaphone in Sobriety, Obesity & Growing Old... If you stop to think about the origins of animation, you’ll inevitably conjure up the image of the first global star of animated films: Felix the Cat, created by Otto Messmer and produced by Pat Sullivan’s studio. Felix’s tail is often transformed into a walking stick, umbrella, exclamation or question mark. Kentridge’s black cat could be the great grandson of Felix, who was designed as a veritable machine of poetic transformations and visual gags: a playful vector questioning the solidity of the world and pointing out the temporariness of everything, even dogmas.

Multiplying William Kentridge

During his masterclass at TedxJohannesburg, Kentridge screened a video showing four versions of him in his studio, all speaking at the same time, stumbling over their words and generating a playful cacophony that, in a sense, illustrated his scepticism about the format of the masterclass delivered from an ivory tower of knowledge that rules out any possibility of doubt or vacillation; in short, every false step. Kentridge is sceptical about anyone who is too certain about their ideas, about those who think they possess the truth. Instead he favours slips of the tongue, free associations, gaps in the discourse, and even what he calls creative and imaginative misinterpretations or mistranslations. He states that a five-year-old would be better able to get to the heart of his artistic discourse than a doctor of fine arts.

Perseus and SibylWilliam Kentridge, , 2020, film still. Courtesy of the artist

Perseus and SibylWilliam Kentridge, , 2020, film still. Courtesy of the artist

Kentridge’s taste for split personalities and multiplication goes way beyond the superimposition of his features on the figures of Soho Eckstein and Felix Teitlebaum. In a series of video films made during lockdown, the artist is split into two versions of himself: Kentridge the author and Kentridge the viewer. Inside his working studio which is, at the same time, a space for play and experimentation, a liminal territory between light and shade and a sort of crystallisation of Kentridge’s brain, the two figures argue and often pick apart some of the ideas set out in the “Six Drawings Lessons”. This can be seen in the piece Perseus and the Sybil that concludes the first section of the exhibition William Kentridge: That Which Is Not Drawn. The artist has described his studio as “a safe space for stupidity”, a limbo in which he walks obsessively on a peripatetic route inviting images and ideas to collide with each in order to produce new conceptual short circuits, or new revelations. There is a performer inside William Kentridge and, therefore, a clown: the artist studied under Jacques Lecoq, interiorising the control of the body and physical expression that forms the very core of many of his formal solutions and aesthetic discoveries. Often, when people talk about Kentridge, the overwhelming power of the historical benchmarks he uses seem to relegate to the background one of the most important facets of his approach to his work: his sense of humour, a cornerstone of a whole that clearly emanates from his great skill in achieving revelation along paths of an apparent – yet tremendously productive – stupidity.

Words against entropy

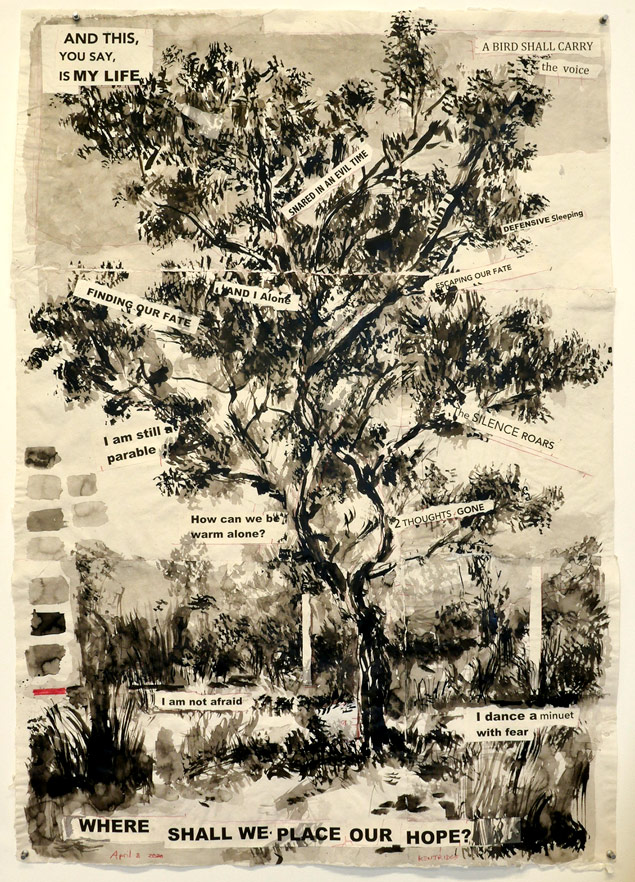

A tree rises up in William Kentridge’s drawing for the front page of the Dutch newspaper Het Parool. He produced the drawing last April, at the height of lockdown, when the newspaper had invited a series of artists and designers to send out messages of encouragement as part of a campaign entitled Hou Vol (Let’s stay strong). At the bottom of the drawing, we can read “Where shall we place our hope?” The tree is dotted with many other messages: “I am not afraid”, “I dance a minuet with fear”, “How can we be warm alone?”, “I am still a parable”, “The silence roars”, “2 thoughts gone”, “Finding our fate”, “Escaping our fate”, “Snared in an evil time”, “Defensive sleeping”, “And I alone”, “A bird shall carry your voice”, “ And this, you say, is my life”. The written word is an intrinsic part of Kentridge’s work, either in his animations, stage designs, tapestries or drawings: a written word that always adopts a fragmented form, as if we were looking at the pieces of an exquisite corpse or a heap of fragments of lost songs or poems we can no longer recognise.

A Natural History of the StudioWilliam Kentridge, drawing for (Where Shall We Place our Hope?), 2020. Courtesy of the artist

A Natural History of the StudioWilliam Kentridge, drawing for (Where Shall We Place our Hope?), 2020. Courtesy of the artist

In his piece Perseus and the Sybil, William Kentridge evokes a mythical image that gives these words, which are supposedly detached from the discourse to which they belong, an enlightening meaning: at the entrance to the cave where the Sybil wrote about the fate of mortals, a strong wind blew away her sheets of paper. This meant that when the mortals managed to grab one of the sheets they couldn’t be sure if the fate written on it was theirs or someone else’s. One of Kentridge’s creative methods consists of writing sentences and words on pieces of paper: annotations that he jumbles up and reassembles, not because randomness is a principle he has any faith in, although he is interested in breaking down language structures, as proposed by the avant-gardes, spearheaded by Dadaism. In fact, Kentridge conceives his art as a fight against entropy, as a struggle against the chaos of the world in search of meaning. Some of the messages in his drawing for the front page of Het Parool resonate more strongly, given the situation at the time when we were all equal in our solitude and vulnerability. However, when viewed as a whole, they don’t relinquish contradiction and paradox: “Finding our fate” / “Escaping our fate”. Kentridge’s work chooses not to set in stone any of its potential meanings and this may be the decisive factor that explains the universality of his art. Our fate may be written on one of Kentridge’s pieces of paper but it won’t be easy to find. What seems clear, however, is that his words apply to all of us, in equal measure.

William Kentridge

That Which Is Not Drawn

9 October 2020 — 21 February 2021

With animation, drawing, cinema, music and theatre, South African artist William Kentridge has built a sprawling work, combining techniques and disciplines. The exhibition is a unique chance to see some of Kentridge’s most iconic works: large-format tapestries and the full series of 11 short animation films, Drawings for Projection. The CCCB is the first place in Europe to premiere Kentridge’s latest film, City Deep.