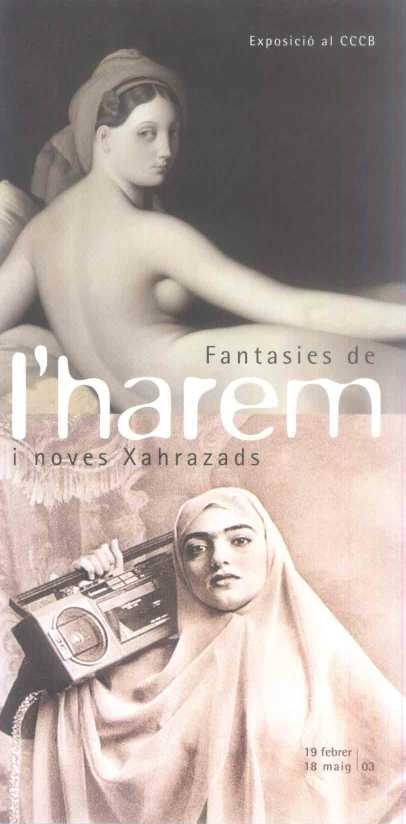

Exhibition

Harem fantasies and the new scheherazades

It is surprising how many Western men smile when they hear the word harem. The only explanation is the fascination that the harem has excited in the Western imaginary since the eighteenth century. Orientalism has been a thought-provoking theme for the many Western artists to have painted an idyllic view of the harem and its women.

In fact the word harem, referring to a family institution in Islamic society, describes a private space where womenfolk are kept closed away from public life. Eastern men's fantasies centred on women with names, such as Scheherazade, who fought for her freedom using stories as her weapon, or Shirin, the Persian heroine who crossed continents on horseback - a real contrast with the passive, anonymous odalisque of Western fantasy.

This contrast of views is the central theme of the exhibition, conceived and directed by Fatema Mernissi, author, among other books, of Scheherazade Goes West: Different Cultures, Different Harems. As a counterpoint, the new Scheherazades, contemporary artists from an Islamic background, are women who fight for their freedom in every sense, who take risks and expound their intimate, rebellious thoughts, using the personal visual language of their work to voice their protest.

Curators: Fatema Mernissi

While the East locked up its women and imagined them free, the West left them free and imagined them locked up. The word harem is derived from haram, the illicit, that which religious law forbids, as opposed to halal, that which is allowed. As a family institution it represented a private space with strict codes and rules that had to be observed, and where womenfolk were closed away so that they could be controlled, as they were seen to interfere with and upset masculine emotions and reason. Their confinement turned them into the enemy, as only something that is regarded as a danger is locked up. In Western eyes, conversely, the harem is the projection of a fantasy, of a desire - ultimately, of the imaginary. It is a blank space in which dreams can be projected. In the absence of constrictions and prohibition, the woman who inhabits it becomes an object of sexual pleasure, who appears to be happy and take pleasure in her confinement.

Taking as its basis the reality and the myth of the harem, the exhibition strikes a contrast between Western and Eastern iconographies. The various approaches reveal the role of women in Islamic society, and the fascination that the theme of the harem awoke in Western artists in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Western iconography is just one of the views presented in this exhibition. The other is, precisely, the viewpoint of the society which produced the harem. And, finally, the exhibition includes the gaze of contemporary women artists from that same society who, by means of their work, radically challenge the traditional view of women.

1.- SCHEHERAZADE

Scheherazade, heroine of the word

Scheherazade, the daughter of a vizier, sets out to put an end to the killing of young women started by the sovereign of Baghdad. She decides to marry him in order to enthral and disarm him with the stories she tells. To transform the mind of a criminal who is prepared to kill by telling stories is an extraordinary exploit. In order to do so, Scheherazade has to master three strategic skills: control of a vast quantity of information she has learned from reading history and poetry books, the ability to clearly understand the mind of a criminal, and the decisiveness to act with sangfroid, bringing into play all of her resources of intelligence, beauty and literary skill.

This heroine of knowledge is mythical in the Arab world. But what happened to her when she went West? What changes did she undergo when she was seen and read by Western artists? We know the exact date on which Scheherazade crossed the border. It was in 1704, and her first stop was Paris: the first European translation of The Thousand and One Nights.

Scheherazade goes West

Between 1704 and 1717, The Thousand and One Nights was translated by the French diplomat and scholar Antoine Galland, secretary to the Portuguese King's ambassador in Turkey. The fascination aroused by the publication of this work in many European countries was so great that it could be said to shape the Western imaginary of the East. It was another famous translation, the Arabian Nights of Richard Burton (1882-1886), that reinstated the erotic passages that Galland had suppressed.

Surprisingly, the intellectual Scheherazade disappeared from all of these translations because, apparently, the Western mind was only interested in adventure, magic, exoticism and sex. For a whole century, Western interest in The Thousand and One Nights was limited to its male heroes, such as Sindbad, Aladdin and Ali Baba.

The imperial harem of Topkapi

It was the harem of Istanbul's Topkapi Sarayi that inspired hundreds of Orientalist fantasies. Western presence in this privileged enclave remained despite the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Istanbul, the centre of the Ottoman dynasty, continued to be a place of reference for European traders and travellers, the city that opened the doors to the East and offered the most emblematic image of the harem.

The harem of European travellers

The reading of The Thousand and One Nights saw the start of a Romantic movement: travellers all compared their own descriptions of the East with Galland's translation. European travellers proved to be particularly fascinated by a place where few could ever hope to be admitted: the harem. As the legendary traveller Lady Montagu wrote in her Letters (published in 1763), Western men's descriptions of the harem lacked authenticity and veracity, as men were forbidden to enter: 'It may surprise you to receive this description, so different to those with which the common travel writers have regaled you, who love to speak of that which they know nothing. Only for very special reasons or on extraordinary occasions do Christians have the opportunity to be admitted into the house of a nobleman, and their harems are always prohibited terrain. They can, therefore, speak only of the exterior part.'

2.- VIEWS OF THE HAREM

Living or seeing the harem

It is surprising how many Western men smile when they hear the word 'harem'. Yet 'harem' is not just a synonym for the family as an institution; we would never think to associate it with something entertaining. The only explanation is the obsessive fascination that the Imperial Ottoman harem excited in the imaginary of Western painters since the eighteenth century, and has continued to do up until the present day.

The dancer

In Voyage pittoresque en Algérie (1845), Théophile Gautier writes: 'The Moorish dance consists of the constant snaking of the body, twisting of the loins, swaying of the hips, arm movements waving scarves; the face faints away, the eyes are absorbed or flaming, the nose tremulous, the lips parted, the breast oppressed, the neck bent like that of a dove overcome with love; all of this undoubtedly represents the mysterious drama of the voluptuousness for which the entire dance is a symbol.' The theme fascinated Orientalist painters, despite the fact that many of them, like Marinelli (1819-1892), had never visited the East. The almehs ('instructed women') were reciters of poetry, but by the nineteenth century the word had evolved to refer to the dancers, also considered prostitutes, as proclaimed by the title of Bouchard's painting (1853-1937).

A prison like a garden

Why did the Muslim forefathers build palaces within walls with gardens to confine their women? Only weak men, convinced that women had wings, could create something as drastic as a harem, a gaol in the guise of a palace.

The harem in prints

Field Marshall Schulenburg commissioned Antonio Giovanni Guardi (1699-1760) to produce a series of quadri turchi to decorate the Oriental salon of his Verona residence. To carry out the commission, Guardi used a collection of prints of harem life reproducing paintings by a Franco-Flemish artist, the official painter of the Ottoman Sultan.

Educating body and mind

'The Caliph asked her, "What is thy name?" "My name is Tawaddud." "O Tawaddud, in what branches of knowledge dost thou excel?" "O my lord, I am versed in syntax and poetry and jurisprudence and exegesis and philosophy; and I am skilled in music and the knowledge of the Divine ordinances and in arithmetic and geodesy and geometry and the fables of the ancients. [...] I have studied the exact sciences, geometry and philosophy and medicine and logic and rhetoric and composition; and I have learnt many things by rote and am passionately fond of poetry. I can play the lute and know its gamut and notes and notation and the crescendo and diminuendo. If I sing and dance, I seduce, and if I dress and scent myself, I slay. In fine, I have reached a pitch of perfection such as can be estimated only by those of them who are firmly rooted in knowledge.'

'Tale of the Salve Girl Tawaddud', The Arabian Nights, translation by Richard Burton

The secret of the hammam

The ritual of bathing as the ennobling cleansing of the body, so present in The Thousand and One Nights, is a concept absent from Christian tradition. It is no wonder, then, that in their attempts to represent the erotic fantasy of the East, many Western artists became obsessed with showing female nakedness in the hammam, distorting its original meaning.

Jean-Leon Gérôme (1824-1904), in his fascination with the East and its legends, produced a series of paintings which were to make him famous. His student, Lecomte de Noüy (1842-1929), and many other painters had recourse to this imaginary apotheosis of the hammam as a libidinous space to be observed with delectation: the most inaccessible place for the male eye, that the painter decided to reveal.

Odalisque with man in the background

It was not usual for male figures to appear in pictorial representations of the harem by Western artists. The odalisque of Marià Fortuny (1838-1874) is all the more mysterious for this reason, immersed in a dense, erotically charged atmosphere, with the hazy figure of an Arab man playing music in the background. The same misty warmth clouding the senses is visible in Benjamin Constant's painting (1845-1902). Marià Fortuny travelled to Morocco on various occasions to produce his Orientalist works, though he painted his odalisque in a studio in Rome. Constant also travelled to Morocco and to Spain, where he became acquainted with Fortuny's work.

Women with and without a name

The fantasies of Eastern men centred on women with names, active women such as Scheherazade or the Persian heroine Shirin, a woman who escaped from the harem where she had grown up every time she fell in love. A woman capable of crossing continents astride her horse, hunting wild animals. A real contrast with the passive odalisque of Western fantasy, with no real life and no name.

What would have happened if Ingres had come face to face with the active woman Shirin in the Bois de Bologne? He would probably have made her dismount, taken away her quiver of arrows, her caftan and her clothes, and made her pose in silence.

In silence

Despite never having travelled to the East, Ingres (1780-1867) was familiar with Persian miniatures. The Odalisque in Grisaille, a new version of La Grande Odalisque, is one of the foremost references in Western representation of the eternal nameless female, of abstract woman, a creature reserved for sexual use. Ingres was very impressed by the travel notes of Lady Montagu describing Eastern women: 'Among them there are some who are as well proportioned as the goddesses drawn by the pencil of Guido or Titian, most with lustrous white skin.' The odalisque as goddess: an image that was to survive the passage of time intact.

The lovers

Western men did not represent themselves in the harems they painted. Eroticism in Western painting has always consisted of a male spectator observing a naked woman whom he himself has immobilised within a frame. The painters of Islamic miniatures, conversely, represented love and the lovers, man and woman, and the dialogue they made possible. To love is to learn to cross the line in order to face the challenge of difference.

Woman and desire

Calling a life model an 'odalisque' was a way of justifying her nakedness, her blatant eroticism. For Boucher (1703-1770), a vague allusion to Eastern fashions - a scarf or the pose of the reclining woman - was enough to give his 'odalisque' (probably the adolescent lover of Louis XV) the necessary hint of the exotic. Chassériau (1819-1856), under the strong influence of Ingres, was to repeat the same strategy: the Orientalist theme (a turban, an item of clothing, a gesture) was an infallible resource in painting naked women in an attitude of desire.

A domestic harem

Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) is the only Western painter who is reliably known to have had access to a harem, albeit a domestic one. A friend of his, Victor Poirel, an engineer who worked for the port authorities in the Algerian capital, managed to get one of his employees to secretly introduce Delacroix into his house, where he had a small harem. This is how Poirel remembered the episode: 'The women, forewarned, had dressed up in their finest clothes and Delacroix drew watercolour sketches which he later used to paint Les femmes d'Alger. He was as though intoxicated by the spectacle before him.'

This series of sketches had an enormous influence on the Orientalist trend and on other painters who took up this iconography, such as Manet (1832-1883) and Matisse (1869-1954). After Matisse's death, Picasso (1881-1973) picked up the theme: 'Matisse has bequeathed me his odalisques.' And, by way of homage to his departed friend, he frenziedly produced his series inspired by Delacroix's originals.

3.- THE LAST HAREMS

Matisse and Ataturk

Matisse completed his painting of the Odalisque with red trousers in 1921. This is an important date in Muslim history, being the year of liberation of Turkish women. While Matisse was painting them as slave girls in a harem, in the context of a nationalistic struggle Kemal Ataturk was proclaiming the laws which gave the women of his country the right to education, to vote and to hold public office.

The odalisque with red trousers

Matisse (1869-1954) spent the winters of 1911, 1912 and 1913 in Tangiers, an experience which, as he himself comments, represented an evolution of his work that reflected the power of seduction that Islamic art and its decorative freedom had over him. In 1917 the painter settled in Nice, a place he was rarely to leave. And there, in the south of France, Matisse felt that he had recovered the lost light of Morocco, and began a series of paintings with an oriental influence, featuring female models reclining amid ornamental throws and hangings.

Souvenirs of the harem

Thanks to its supposed documentary value and scenographic power, photography turned the myth of the harem into serialised fiction. Hollywood, too, became a factory of female stars on a par with the odalisque tradition. Some were based directly on the Orientalist fashion, but at the same time passive attitudes were introduced of reclining women as objects of desire.

With the Qajars

The Qajar albums: the royal harem

In the mid-nineteenth century, the fourth Qajar king (or shah), Nasir al-Din Shah (1831-1896), compulsively had his harem photographed, with its women - his mother, wives, daughters and favourite concubines - and its eunuchs, jesters and dwarves. Never before had a king photographed his andarun (the women and children's quarters), and the resulting images conflict with the female stereotypes surrounding the theme. Until very recently the Qajar albums were kept hidden in the photographic archives of Golestan palace in Teheran. They are on show here for the first time.

4.- THE NEW SCHEHERAZADES

Scheherazade is above all an artist: a woman with imagination, inspiration, originality and talent. Here we show the work of her successors in order to explore the way in which Eastern women today enrich contemporary society by using a personal visual language that challenges the very basis of traditional attitudes to women in the Near East and North Africa, transgressing sexual taboos and the sinister power of domestic objects. These new Scheherazades take risks and bravely expound their intimate, rebellious thoughts. With imagination, talent and a great sense of humour, they assert their identity and deconstruct the Orientalist myth of the voiceless woman. By so doing, they blaze a trail for future generations to challenge established social conceptions and introduce their own interpretation of beauty and love.

Stratified searches

These works constitute a critique of Orientalist fantasies: the female form as a fetish. They question the traditional representation of women in Western art and advertising in our consumer culture.

Jananne Al-Ani (Iraq, 1966) and Houria Niati (Algeria, 1948)

The beauty of paradoxes

Photography can be very flexible in countries where there is censorship, and is therefore one of the media preferred by many Iranian artists. By means of their exploration of the inherent paradoxes in the imposition of old religious principles in a society that cannot evade modernity, many artists have turned this form of expression into metaphors for life.

Malekeh Nayiny (Iran, 1955), Shadi Ghadirian (Iran, 1974), Nadine Touma (Lebanon, 1972) and Ghazel (Iran, 1966)

Weaving erotic taboos

For centuries, women expressed their artistic creativity in anonymity: nomads wove carpets and wedding veils, and made domestic utensils and pottery. Urban women embroidered sumptuous cloths to give colour, form and texture to their domestic surroundings. They were the unsung visual guardians of the East.

Selma Gürbüz (Turkey, 1960), Ghada Amer (Egypt, 1963) and Raeda Saadeh (Palestine, 1977)

The secrets of decorative motifs

This is a personal history of loss, strictly reduced to the abstract in the form of window lattices (mashrabiyeh), where stories are whispered through railings that separate East and West, women and men, Muslims and Christians, truth and lies. In the West, they are celebrated for their beauty, the skill involved and the quality of their pure, intricate abstract forms, whereas the Eastern spectator sees in them elements of confinement and segregation.

Susan Hefuna (Germany, 1962), Samta Benyahia (Algeria, 1944) and Zineb Sedira (France, 1963)

Shirin Neshat (Iran, 1956)