Exhibition

The European savage

Although for some time now we have associated the term savage with non-Western primitive people, the concept is a European creation of Greek origin that applied the term to individuals who did not fit into civilised society: brutal, primitive, threatening and dangerous beings who lived very near, but outside the polis and its regulations.

The exhibition is the product of the theses developed by the anthropologist Roger Bartra in his books Wild Men in the Looking Glass: Mythic Origins of European Otherness (Michigan University Press, 1994) and The Artificial Savage: Modern Myths of the Wild Man (Michigan University Press, 1997), and by the writer Pilar Pedrazain La bella, enigma y pesadilla (Tusquets) and Máquinas de amar (Valdemar). The CCCB has invited these two intellectuals to curate the exhibition we present.

Although for some time now we have associated the term savage with non-Western primitive people, the concept is a European creation of Greek origin that applied the term to individuals who did not fit into civilised society: brutal, primitive, threatening and dangerous beings who lived very near, but outside the polis and its regulations.

The concept of European savage has changed with time. The Greek savage was an ambiguous creature, half human, half animal, related to the gods (the centaur, satyr, Cyclops), who lived in nature and was without aspirations of conquest, unlike the Barbarians. In the Middle Ages, the savages became wild men and hermits, covered with hair. With the conquest of the Americas, entire peoples fell victim to this commonplace, which erased their human characteristics and made them hard to identify. Then, in the 18th and 19th centuries, with the advances of science and a greater knowledge of the body and mind, the savage slipped through the internal chinks of Western consciousness. Then it became the 'savage within': the part of ourselves that we do not recognise, the unknown monster that lives inside us.

Today, the savage embodies the individual who lives among us but responds to an otherness that we cannot quite assimilate, the Other who threatens our way of life (down-and-outs, the underprivileged class, emigrants, urban tribes, etc.).

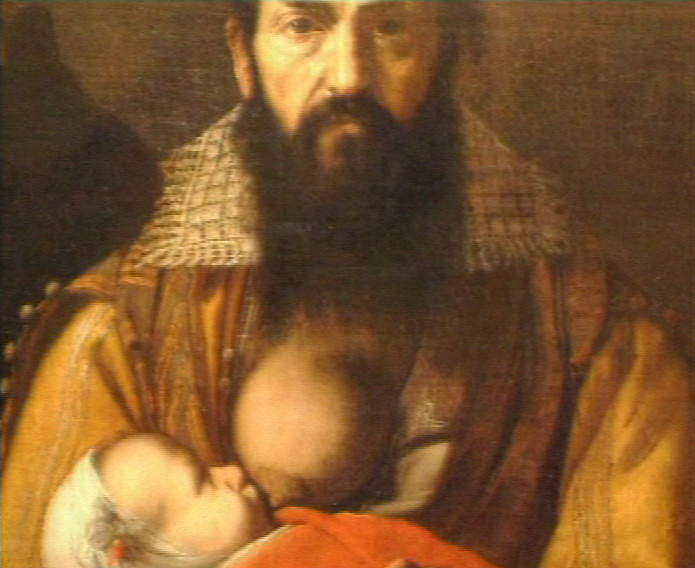

The exhibition presented by the CCCB looks at the iconographical representation of the figure of the European savage in art: Ribera, Goya and Buñuel; Dürer, Mantegna and Bocklin; Salvatore Rosa, Gustave Moreau and Cindy Sherman; Swift, the Marvel 'factory' and George F. Watts... And in all of its forms: satyrs and centaurs, hermits and wild men, witches and yahoos, elephant men and bearded ladies, and popular heroes like Tarzan and the Panther Woman.

Curators: Roger Bartra, Pilar Pedraza

Since ancient times, the forests, islands and deserts of the European imagination have been populated with wild men and women. Europeans have always been convinced of the existence of these savages, despite the fact that they are mythical, imaginary beings. Savages embody one of the most deeply rooted beliefs of Western culture: the idea that very close to us, or within us, the Other exists: a world populated by primitive, threatening and dangerous beings who are not fully human. They are similar to us, but marked by an otherness which distorts them or steals their soul, conscience, speech and civility. However, in some cases, these beings are equipped with an unsettling intelligence...

European savages are hybrid, abnormal characters who combine human features and beast-like attributes in a single body. Their physical characteristics vary according to the regions and epochs, but, in most cases, their bodies are covered with hair and, at times, they have other animal features, such as hooves, a tail or ears. Their human side shows them to be white with clearly European features. They are not a representation of distant and exotic peoples. Neither are they the result of the interference of the demonic in human affairs. They are the presence of nature within the heart of culture and of the bestial within the civilised. They also reduce plural otherness to a single stereotype.

1.- BETWEEN MAN AND BEAST

A.

The ancient Greco-Latin and Judeo-Christian civilisations converge in the figure of the medieval and Renaissance homo sylvestris. This savage figure is part of an alternate and parallel humanity, which does not descend from Adam and Eve. It is not born with original sin and, therefore, the inhabitants of the savage world are lacking in shame, have unbridled sexual instincts and are naked.

These European savages are usually unable to talk; they carry clubs, live in deserted places, in the mountains, forests and on remote islands. Literature has portrayed them as the most troubling characters: Caliban in Shakespeare's The Tempest and the mountain-dwellers who attack the pilgrims in The Book of Good Love by the Archpriest of Hita.

At times, hardships and unhappy love affairs led to the transformation of a knight into a true savage who withdraws, naked, to the solitude of the forest, where he lives, sometimes tormented by sadness and, at other times, possessed by fury, like Cardenio described by Cervantes and Orlando portrayed by Ariosto.

B.

The earliest artistic depictions of the European savage occur in Greek culture. The images of satyrs and centaurs who pursue nymphs and are driven insane by wine, have left a permanent imprint on European art. Greco-Roman mythology has bequeathed to us the idea of an aggressive nature which threatens culture with the exuberance of wild and fantastic beings.

The fearsome Amazons, the formidable one-eyed Cyclopses, the sileni, the lubricious Roman fauns, the frenzied maenads or bacchantes, and the wild nymphs who inhabit the streams and springs of the forest must be added to the list of ancient savages.

These wild, mythical figures left their physical and moral imprint on the stereotypical image of the naked savages of the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

3.- TRAGICOMEDY OF THE SAVAGE

The myth of the European savage is not static. One of its most extraordinary mutations took place at the end of the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance. The violent, aggressive savage became a gentle, noble person who led a peaceful family life. The sequence of two engravings by Dürer and the painting by Altdorfer depict this new situation against a theatrical, almost cinematic backdrop. During the first act we are presented with the surprising paradox: the satyr is a happy family man who plays an instrument to delight his wife, a beautiful nymph, and his young son.

In the second act, a violent woman, the only clothed character and a seemingly civilised presence, furiously attacks the satyr's family. However, a muscular, handsome savage appears who places his club between the woman and the frightened couple in order to protect them. The child has fled in terror. There is another interesting mutation: the savage is no longer hirsute.

The mystery of these two engravings by Dürer is solved by Altdorfer's painting, dating from 1507, which constitutes the third act: the satyr's family regains its composure, while the naked savage pursues and catches the clothed woman, whom he may abduct and rape in a fourth act which we cannot see. However, we can imagine that the savage is taking his revenge on the civilisation which has provoked him...

4.-THE DOMESTICATED SAVAGE

Those trends which viewed the savage as an escapist alternative to the evils of civilisation, came across a paradox: it was necessary to "civilise" the savage in order to make him an idyllic model. In this tapestry from Basel, the savages have a child-like appearance and devote themselves to farming activities as if they were an innocent game.

Wild men and women have left the forest and, sporting bright blue and red tufts of hair, devote themselves to productive activities. The tapestry, which was made around 1480, reveals the multicoloured panorama of a peasant utopia.

A veil of pastoral and rural bliss fully conceals the savage as an uncontrolled erotic power, as the source of unbridled natural violence and a dangerous crack in the cosmic order through which chaos may spill out. Savages began to be domesticated towards the end of the Middle Ages. The ferocious being becomes the symbol of an idyllic life, a creature who lives in harmony with nature.

These wild folks prefigure the noble savage extolled by the enlightened philosophers of the 18th century. Before Rousseau, the myth of the savage had explored the idea that original beings were not evil by nature.

5.- GOD'S SAVAGE

Christianity absorbed the pagan idea of the savage and made him part of the ancient religious tradition, rooted in Judaism, which had created an abstract and moral idea of savage otherness. This idea was took shape in the image of the desert. Here, the Christians confronted a barren wild landscape, full of temptations and dangers, in order to test the strength of their faith. During the test, they often became savage saints, who lived naked in the desert, their bodies covered in hair. In Christian imagery, John the Baptist, who had come from the desert, was presented as a wild being. The images of Saint Jerome repenting and Saint Anthony being tempted, both of them in the desert, are well-known.

In the wild void, the primitive lives of the monks and hermit saints heralded communion with the divinity. This is the case of Onofre, the Theban monk, who withdrew like a savage to a cave in the desert. Others isolated themselves at the top of columns. Luis Buñuel's masterpiece, Simon of the Desert, is a surrealist take on the existence of these Theban ascetics.

The most famous wild saints are Mary Magdalene and John Chrisostome. Both were associated with lust and went through long periods of repentance as hirsute savages in the solitude of those places abandoned by man.

6.- SPECTACLE AND DISEASE

For centuries, royal courts and fairgrounds, as well as circuses and museums, have exhibited exotic people and those afflicted with abnormalities. Indians, shipwreck victims, wild children, hirsute men and women and deformed creatures have been presented and kept as savages or animal hybrids. The baroque period was their first golden age, and their second was the 19th century when astute businessmen, such as Phineas Taylor Barnum, launched the craze for freakshows. Since the 20th century, science has taken care of these creatures. The so-called wild children bear the greatest resemblance to the European savage, and several of them have been encountered in modern Europe. Wild children had been abandoned because of their poor mental development or suffered from this condition after being abandoned, and were adopted by female animals. They wandered the countryside until they were captured, exhibited under the big top, and maybe violated by science, to be finally adopted as the subject of films, at the other end of the spectrum from superheroes.

7.- THE WILD WOMAN

The modern age has imagined that there are dangerous orifices within the fabric of civilisation which let in the savage forces of nature. According to the misogynist thinking of bourgeois culture, these openings are usually feminine in nature. As a mother, woman is supposedly closer to nature than man. Her uterus is a tunnel which is directly connected to uncontrollable savage forces. Woman becomes a potential savage from the moment she is no longer considered totally human, as occurred in the Middle Ages, or when her human qualities are considered inferior to those of man, as many philosophers and scientists proclaimed in the 19th and 20th centuries. This savagery manifests itself in the witches' coven as well as in the "mystical" expressions of hysteria.

8.- THE INNER SAVAGE

A vampire/impaler may be crouching behind the impassive gaze of a Renaissance prince. In fairy tales, ogres lie in wait in order to cut up and devour people who are sleeping. A drink of alcohol turns a mother into a maenad. A wild animal is concealed inside a beautiful young foreign girl. A well-intentioned scientist unleashes his evil other self. The modern age has taught us a vital lesson: that the savage we thought dwelt in the mountains and uplands really lives inside us and it is easier to unleash him than send him back to his lair. The arts and sciences, such as psychoanalysis, anthropology, symbolist paintings and the cinema, have taught us a great deal in this respect, but only a broadly based, open awareness of humanity can prevent us from falling into the temptation of branding others -rather than ourselves- as savages, which is usually an excuse for the worst kind of abuse.